A 1777 Johannes Plenius Square Piano: Restoration & Context

In 2023, I acquired an early English square piano inscribed “Johannes Plenius, London fecit 1777”. This instrument will serve as one of the principal keyboards in my ongoing Johann Christian Bach complete-works projects, and I expect it to become a central voice in other late-eighteenth-century repertories that sit naturally at the boundary between the harpsichord and the fortepiano.

The piano arrived in notably original condition: structurally coherent and historically legible, yet plainly worn from a long domestic life. One could easily imagine it having offered, at times, a quiet refuge for dust, detritus, and even mice. Since its acquisition, it has been thoroughly cleaned and is now undergoing a careful restoration by Paul Kobald in Amsterdam, with completion planned for March 2026. The work returns it to reliable playing order while preserving the telling fingerprints of early English square-piano design.

What keeps drawing me back to these earliest squares is something that later piano culture — focused on power and brilliance — often overwrites. The delicacy of these early pianos is not a defect but an aesthetic. In galant music they can be irresistibly charming, even sweet, and they reward the player with an unusually direct relationship between touch and attack.

The square piano in its condition from the auction house: pre-restoration.

To play well on an early English square is to accept that pianistic “power” is beside the point. Sensitivity and delicacy, not overwrought brilliance, become the marks of refinement. The technique required often sits closer to that of the clavichord rather than later virtuosity: economical key motion, a careful release, and meticulous control of timing and articulation at the instant of contact. At their best, early squares can sound like a kind of large clavichord: brighter, cleaner, and more projecting, yet governed by a similar intimacy of touch. Depending on register and room, they may also recall a more “dynamic” harpsichord, with a clear attack that nonetheless admits expressive gradations unavailable to a plucked action. For that reason, I find early squares especially persuasive for keyboard repertoire well into the 1780s. They offer a compelling, and very likely more historically typical, alternative to the modern early-piano habit of defaulting to Viennese and South German instruments (Walter & Stein) for nearly everything. Those instruments are wonderful, but they can become aesthetically over-determinative. Their singing sustain and coloristic resonance sometimes encourage a post-Romantic legato ideology that sits uneasily with the clipped, speaking, and socially domestic origins of much late-eighteenth-century keyboard culture. The English square piano points to a different center: London’s commercial modernity, its middle-class market, and the portability of a fashionable new sound world.

The English square piano as a 1760s innovation

Original Zumpe square piano in the Cobbe Collection, London c. 1769

The early English square piano was a design breakthrough that helped turn the piano from a specialist curiosity into a widely adoptable domestic commodity. A pivotal figure was Johannes Zumpe, who introduced a small rectangular pianoforte design (later called the “square piano”) that proved affordable and attractive to a growing market beyond elite court circles. The Metropolitan Museum of Art summarizes the shift succinctly: Zumpe introduced the square design around 1766, and it quickly became associated with large-scale manufacture and the tastes of the expanding middle class.

Technically, these instruments commonly used what organological literature often describes as the English single action: a straightforward mechanism engineered for reliability and economy rather than for the later grand ideal of repetition and power. In a typical early Zumpe, hand stops could operate dampers in separate regions (treble and bass), offering control over resonance. Just as importantly, the model proved socially portable. Many makers and collections note how quickly the Zumpe pattern was taken up by other workshops and how broadly it circulated through subcontracting in London, as well as export and imitation across Europe.

Within this world, Johann Christian Bach mattered not only as a composer but as a visible broker of taste in Georgian London, whose public choices helped make the new pianoforte socially legible. In asking what keyboard Bach actually used when London advertisements announced a “Solo on the Piano Forte,” Richard Maunder points to the now-famous benefit concert at the Thatched House Tavern (2 June 1768) and frames it as a practical, organological question: was Bach really presenting a small Zumpe-style square in a largely orchestral programme, or something closer to an experimental “grand” prototype?¹ The contemporary advertisement itself is explicit, placing Bach’s solo alongside Abel’s viola da gamba performance.

More revealing still is how Charles Burney narrates the episode in retrospect: he ties the new instrument’s commercial momentum directly to Bach’s arrival and to the concert culture Bach created with Abel, observing that “there was scarcely a house in the kingdom where a keyed-instrument had ever had admission, but was supplied with one of Zumpe’s piano-fortes.” In Burney’s telling, the “virginal-sized” square was not simply a clever technical simplification, but a commodity whose success depended on fashion, networks, and demonstration. That same linkage between instrument-making and cultural sponsorship is captured succinctly by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which notes that Bach, by then the Queen’s music master, “endorsed the instrument in 1768.” If Maunder helps us keep the material question honest (what sort of piano, in what room, under what acoustic constraints), Burney and the Met together clarify why the question mattered. The early London piano breakthrough was as much a story of marketing, prestige, and public advocacy as it was of manufacture.

Although the square piano is often narrated as a London story, it did not remain a London secret. One intriguing marker of its broader reach appears in a detailed Christie's catalogue essay on a late-1770s London square piano associated with Johannes (John) Pohlman. In discussing Pohlman’s prominence among early square-piano makers, the essay states that Christoph Willibald Gluck used a Pohlman square piano at the Paris Opéra in 1772, citing scholarship attributed there to G. Lancaster. Whether this implies ownership, occasional use, or institutional deployment, it fits a broader pattern: squares were fashionable enough, and practically useful enough, to travel, to be recommended by figures such as Charles Burney, and to participate in musical life beyond the English domestic sphere.

The Plenius Family

Margaret Debenham and Michael Cole’s documentary study of pioneer London piano makers reconstructs a dense network of immigrant craftsmanship and entrepreneurial risk in the decades before, and immediately around, Zumpe’s breakthrough in the 1760s. It can be read alongside broader accounts of the period as part of a larger story in which many German-speaking craftspersons (including Zumpe himself) were drawn to London by the prospect of economic opportunity and social mobility that was harder to secure under the more restrictive guild regimes common on the Continent, where the regulation of trades could limit who might build instruments and how readily new designs could be pursued, while London’s comparatively open market promised a plausible route to independence, rapid production, and (at least in the best cases) advancing one’s fortunes.

Rutgerus (Roger) Plenius is among one of these migrant craftsmen. He was a German-born maker who first settled in Amsterdam, but eventually became active in London from the 1740s. Once there, he pursued a strikingly entrepreneurial path. He was one of the first English builders to attempt a pianoforte, and he also made very large, ambitious harpsichords and spinets. Throughout his career, Plenius often promoted speculative instruments (like his “lyrichord,” a sort of harpsichord designed to never go out of tune) and filed patents for keyboard “improvements” (including a 1741 patent and a further patent in 1745, both emerging from a fraught collaboration with Charles Cope). In their account, this inventive drive did not translate into financial stability. Plenius’ debts became tangled enough that bankruptcy proceedings were initiated by a creditor (Mrs Aldworth) and, by the mid-1750s, the court evidence had grown “extremely complex and difficult to unravel.” A telling detail is that, even after Plenius had been declared bankrupt, his reputation could still circulate internationally: in 1761, George Washington asked his London agent to procure “a very good spinet” made by “Mr Plinius,” apparently unaware of the legal proceedings. Plenius, here, seems to be a maker who was widely known, technically ambitious, and yet repeatedly destabilized by the economics of invention.

Within that turbulent family history, Johannes (John) Plenius is generally understood to be Roger’s son, and the surviving documentation places him inside the workshop rather than at its margins. Debenham and Cole note that “John” is explicitly mentioned in court documents in 1757 as having worked with his father from 1737 onwards, which implies an unusually long apprenticeship and suggests that the Plenius “brand” could function as a family enterprise across decades. This makes it tempting to read my 1777 square piano, signed “Johannes Plenius, London fecit 1777,” as the product of a second generation seeking a surer footing in a market that had changed dramatically after Zumpe’s breakthrough. If Roger’s story is marked by high-risk novelty (patents, prototypes, and publicity for instruments like the Lyrichord), John’s most plausible route to stability would have been to embrace the standardized, saleable “Zumpe manner” that dominated London’s domestic trade by the 1770s, when workshops could profit by building to an expected pattern rather than gambling on inventions that required explanation, patronage, and luck.

The archival “trail” for John himself remains fragmentary, and that thinness has encouraged competing theories about where he may have gone or how the workshop name persisted: insurance and directory materials place a John Plenius at identifiable London addresses in the 1760s, while later references thin out sharply; one possibility is simply that the family’s work was absorbed into other shops or continued under relatives, another that instruments bearing the Plenius name circulated through export or resale networks that obscured the maker’s later movements. (A further complication is that some records appear to associate a “John” Plenius with a burial in 1775, which, if it refers to the same person, would force us to consider whether later instruments reflect a workshop continuation, another family member, or a not-yet-fully-resolved documentary conflation.)

My 1777 Plenius in detail

Organologically, the Plenius presents as a classic early square of the 1770s, close in concept to the Zumpe pattern and to other London-made squares associated with makers such as Buntebart, Beyer, Beck, and Pohlman. Its core specifications (as preserved and as restored) can be summarized as follows:

Inscription: “Johannes Plenius, London fecit 1777”

Compass: FF–f⁴ (five octaves)¹

Key coverings: ivory naturals (with typical ebony accidentals)

Action: English single action

Hand stops (3): including a divided damper lift and a buff stop

Interior fittings: no “shade” / dust cover and no internal music desk, so the instrument is likely meant to be used with the lid closed

Lid-closed practice changes how the instrument speaks. In my experience with early English squares, the sound is often more satisfying with the lid closed: action noise recedes, the tone rounds off, and the instrument gains a subtle warmth.

With the lid open, the listener receives a more direct, high-frequency-rich component from strings and action, and mechanical transients become more apparent. With the lid closed, the case behaves more like an acoustic filter and diffuser, softening brittle edges and encouraging a more integrated blend of partials in the room.

In this context, the absence of a string “shade” on my Plenius becomes suggestive. On many later squares, a thin resonating “dust cover” placed over the strings seems (to my ear, as a working hypothesis) to preserve some of that warmth even when the lid is open. That may reflect a practical adaptation for chamber contexts, where the square’s modest carrying power could tempt players to open the case simply to gain volume. I do not present this as settled historical doctrine; it remains a performer’s organological inference that I intend to test explicitly once the restoration is complete and the instrument has stabilized acoustically.

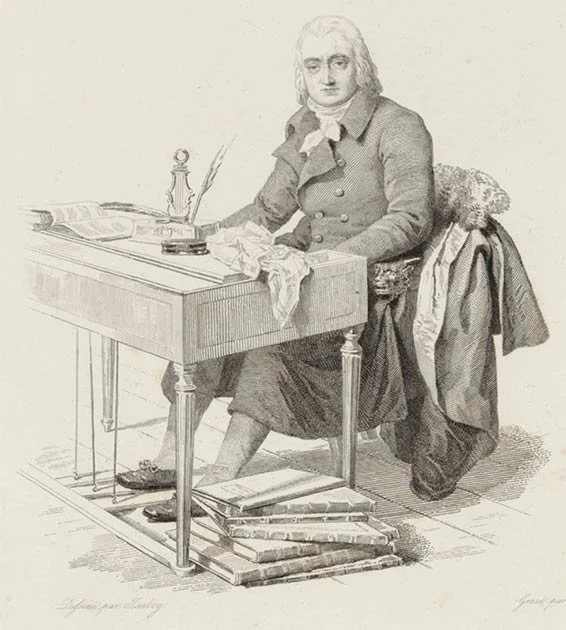

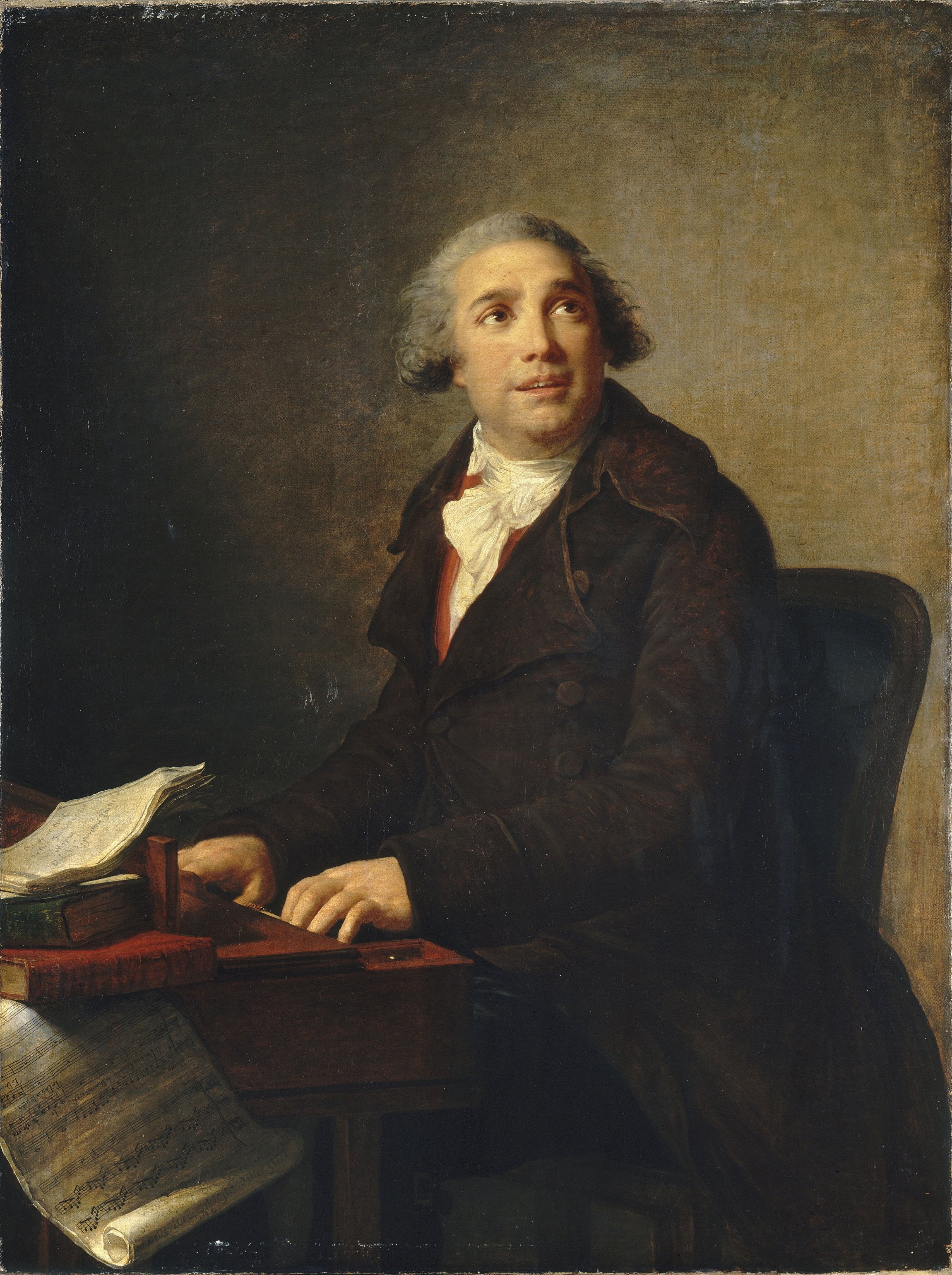

what portraits imply about instruments, posture, and domestic listening

Period portraiture and musical imagery repeatedly place composers and musicians at small rectangular keyboards broadly consistent with the English square-piano family.

Joseph Haydn, in a well-known oil portrait by Ludwig Guttenbrunn, c. 1770. The instrument is distinctly a Zumpe-type English square piano, with the lid hook and hand stops visible.

André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry, in a portrait commonly dated c. 1788, shown at a small French square piano with 3 pedals.

Giovanni Paisiello, painted by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun in 1790 (exhibited at the Salon of 1791), now on long-term loan at Palace of Versailles. The instrument looks distinctly like an English square piano.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, 1733–1810. The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper ca. 1775

A further strand of imagery, including miniatures and domestic scenes from the 1770s, reinforces not only the prevalence of the instrument type but also its setting: the square piano as a fixture of the drawing-room, designed for refined listening rather than public spectacle.

Why this matters for my J. C. Bach complete-works projects (and beyond)

Once the Plenius is complete in 2026, it will function as a foundational tool in my work on Johann Christian Bach’s music. Bach’s London sits at a turning point: harpsichord prestige persists, while pianoforte culture begins to signal modernity in public. The square piano makes audible expressive features that later instruments simply cannot produce as effectively. For these reasons, I anticipate using the Plenius not only for Bach, but also for a wide orbit of late-eighteenth-century repertoire.

References

Charles Burney, “Harpsichord,” in The Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, ed. Abraham Rees (London, 1819), s.v. “Harpsichord,” quoted in Fritzsch, “Introduction,” G226 (2012).

David Debenham and Michael Cole, “Pioneer Piano Makers in London, 1737–74,” Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle 44 (2013): 55–86.

“For the Benefit of Mr. Fisher … Solo on the Piano Forte by Mr. Bach,” Public Advertiser (London), 2 June 1768, quoted in Thomas Fritzsch, “Introduction,” G226 (Güntersberg, 2012).

François Portier, “German Immigrants and the Birth of the Piano in Great Britain: Bach, Zumpe, their friends and the square piano,” XVII–XVIII 64 (2007): 339–40, doi:10.3406/xvii.2007.2349.

Piano Technicians Guild Foundation (Jack Wyatt Museum), “1782 Buntebart Square Piano (London),” accessed February 20, 2026.

British Museum, “Dr Joseph Haydn” (print; museum no. 1887,0722.43), 1792.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Giovanni Paisiello” (discussion of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s 1791 portrait), accessed February 20, 2026.

Christie's, lot essay for “A George III Chinese lacquer and japanned small piano forte … with movement attributed to John Pohlman,” noting Christoph Willibald Gluck’s reported use of a Pohlmann square piano at the Paris Opéra (1772), accessed February 20, 2026.

Richard Maunder, “J. C. Bach and the Early Piano in London,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 116, no. 2 (1991): 201–2.

Swedish Haydn Society, “Portrait of André Ernest Modeste Grétry (au fortepiano),” describing Antoine Vestier’s portrait (c. 1788), accessed February 20, 2026.